It's My Fault and I'll Blame It on Whomever I Want

- UN4RTificial

- Jun 27, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Aug 19, 2025

If you are the type of person who thinks that guilt is something serious, a weight on your conscience or even divine punishment, then get ready.

In this short article, we are going to deconstruct this muse of sleepless nights, because, let's face it, if guilt were money, many of us would be rich - or even worse, many would choose to spend that fortune on the art of transfer.

But what is guilt, anyway?

Everyone knows this beast, which is often the protagonist of life's best and worst dramas. For some, it is a companion that surrounds decisions, stumbles and everyday misadventures. For others, it is an extremely flexible invention, so much so that it can be used as a mask to be worn or removed at will.

We all know that it can be as capricious as a poet's imagination. So, without further ado, I would say that guilt is a feeling that lives on the border between the real and the imaginary. It inhabits the “grey area” of our minds, the same place where information that is “on the tip of our tongues” resides and which we often cannot verbalise.

It arises in those moments when we believe we have made a mistake, that we have done something that displeased someone else or ourselves. The thing is, guilt is a very complex concept, a mixture of moral, social and even biological feelings.

But before we begin, let's refresh our memory by remembering the meaning of this word:

Fault - Responsibility for something reprehensible or harmful caused to another person.

Now, let's take a closer look at this topic.

Responsibility & Guilt - Distant relatives or Siamese twins?

Let's use something that has happened to almost everyone as an example. Being fired. Was it our fault? Maybe. Was it the boss's fault? Perhaps, or probably. Was it the economic crisis? Definitely. Blame always works like a play of light and shadow in an expressionist painting: depending on the angle you look at it, it changes.

And it is precisely because of these different angles that many people insist on confusing blame with responsibility, and vice versa. It seems that people love to lump everything together. Blame and responsibility. Thinking and having thoughts. These different concepts love and hate each other, all at the same time.

Speaking of responsibility, it is something that drives us forward. It is through responsibility that we become aware of the consequences of our actions while looking to the future. Guilt, on the other hand, is more like a cage, trapping us in the past and condemning us to relive our mistakes in an endless looping.

A good example of this would be the view of the strict moralist, Immanuel Kant, who spoke a lot about duty and morality. For him, responsibility is the duty to act according to reason and morality. In this context, guilt would be the weight we feel when we fail to fulfil our duty.

Note that this weight we feel is more related to our perception than to objective reality. But that doesn't mean we should become masters at blaming everyone for everything — even if most people do. The idea here is to reflect on how guilt can be manipulated, used as a sword, a shield, or even a mirror for recognising flaws, but in a more conscious way.

Because when we gain knowledge and control over guilt, it loses its power to torment us, and we realise how much we use ‘it's his/her fault’ as a defence mechanism. Often, without realising it, this act has become a vicious cycle that does not help our development but encourages us to delegate responsibility for our own lives to others.

The Push-and-Pull Game

We still find it difficult to admit that blame has become a national sport, where regardless of the environment or context, the art of pointing fingers is always easier and more practical than taking responsibility for one's own mistakes. This is because blame has been widely used as a bargaining chip for centuries. The reasons are diverse, whether for manipulation, domination or even to overcome some, while others - the real culprits - escape unscathed from the consequences of their actions.

Machiavelli already explained in his work ‘The Prince’ that power is maintained, in most cases, through the art of manipulation, so there is nothing better than ‘blaming’ something or someone in order to maintain control. We live in a world where admitting one's mistakes can mean the loss of status, employment or even affection. Therefore, it is not surprising that taking responsibility does not become a trend.

The Duel of Minds

As we delve into the spiral of unambiguous concepts of guilt, we encounter a fascinating range of interpretations. Different philosophical, religious and psychological schools of thought approach this topic from perspectives that are often conflicting and sometimes complementary.

We will start with Socrates, the guy who said he knew nothing (‘I know that I know nothing’), but at the same time kept repeating that people needed to know themselves (‘Know thyself’). For him, self-knowledge was essential. It was the basis for living well and not something optional, as many people think today. His view is very straightforward: if individuals know themselves, they do not need to feel guilty about their actions.

Well, before we decide to throw this whole story into the common grave of self-indulgence, it is worth remembering Sartre. Yes, the Frenchman with the glasses and the big mind would not let us forget that ‘We are condemned to be free...’. In existentialism, guilt is an inevitable condition that is linked to freedom. And this freedom, in turn, goes hand in hand with responsibility. The choice is always ours, which is why it often comes with the weight of regret and remorse.

Translated into English, this means that guilt can be just a haunting created by our own conscience, which, badly and poorly, tries to control our choices. It would be just a sign that we are truly alive and not a punishment to be avoided at all costs.

Still within existentialism, Simone de Beauvoir spoke of guilt as a natural reaction of the conscience that should not be ignored, but rather confronted and used as fuel for true authenticity and freedom. This more balanced approach tells us to face guilt as a burden that we do not need to carry forever; we should simply let it go and move on.

From a traditional Christian perspective, this idea could sound like heresy. Guilt plays a central role here, being seen as the recognition of sin that requires penance. This concept has shaped Western culture for centuries and gave rise to the concept of paralysing and oppressive guilt that we know today.

Nietzsche comes in strong, saying that guilt is something created by the weak to subjugate the strong. This whole story is nothing more than a power game between what we call ‘slave morality’ and ‘master morality.’ He did not agree with Christian guilt and saw it as a form of repressive mental slavery that prevents individuals from expressing their ‘will to power’ — the desire of every human being, the ‘beyond man’ (Übermensch), the one who breaks the internal and external bonds and becomes who he really is.

To quote our friend Kant again. He saw it all in a more ‘normal’ way, guilt was in the light of responsibility and duty, that is, if we do not do what we should, the feeling of guilt will whip us mercilessly.

Psychoanalysis, on the other hand, talks about subtle layers. Both Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, and Lacan sweep guilt under the rug of our unconscious. They say that guilt emerges from internal conflicts, often unconscious, that drive us to act in search of psychic balance. In this view, guilt is both a symptom and a solution.

Meanwhile, in the peaceful temples of Buddhism, guilt is treated in a more uplifting way. Buddhists see guilt as a feeling to be understood, accepted and overcome so that suffering may cease. There is no divine punishment, only learning and liberation.

All well and good, but really... these contrasts make us reflect on how we view real guilt and invented guilt. Yes, there is also the kind of guilt that we imagine and go around distributing to others.

How do these views shape our decisions and our way of life? What if we started using guilt - and responsibility - as a tool instead of a prison? The choice is ours.

The Supreme Court of the Collective

Michel Foucault, the master of power relations analysis, draws our attention to how society uses social control to maintain its own interests, and guilt is a highly effective tool for perpetuating this control.

When we talk about witch hunts or the Inquisition trials, we remember the ‘angry mobs,’ crowds of people who were often driven only by collective guilt or fear of others and even of the unknown, deciding who should pay for social ‘sins.’

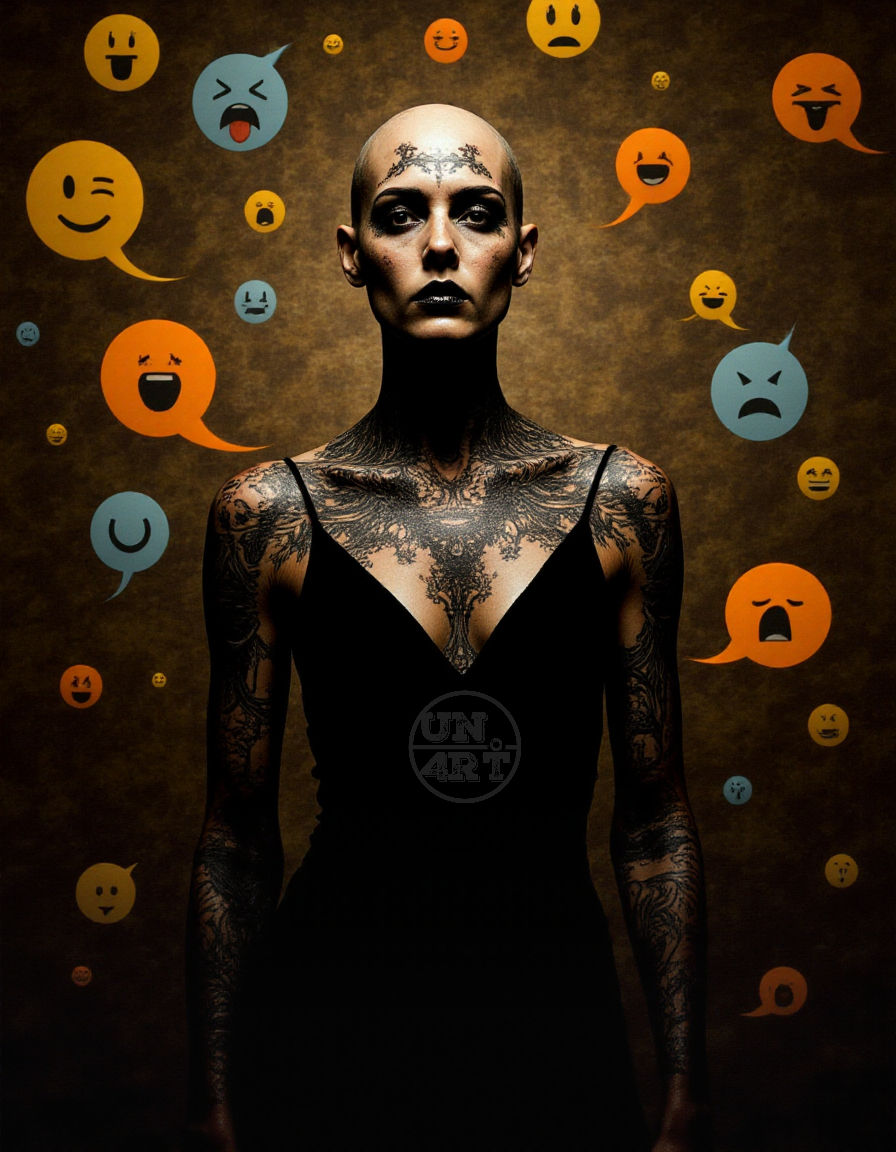

In the modern world, collective guilt appears very clearly on social media, where ‘cancelling’ has become the ultimate embodiment of ‘collective guilt’ and the unbridled transfer of responsibility. Guilt has always been a spectacle, where the public - the masses - are the jury and the executioner, all with a dramatic touch, because who doesn't love a little theatre in the name of justice, right?

Not all blame levelled on social media is true, just as not all criticism is unfair. But how can we identify this when we lack critical thinking skills – because we have not learned to develop them – and when digital sanity is almost non-existent?

The Monster in the Attic

When guilt ceases to be something external and settles within us, it becomes a shadow that follows us every step of the way. This internalised guilt has corrosive effects, affecting our self-esteem, our decision-making ability and even our mental health.

Carl Gustav Jung brought these repressed feelings to light with his concept of the ‘shadow’ - the rejected and repressed parts of ourselves. The accumulation of guilt is often part of this shadow that we do not want to face. Ignoring or denying this guilt and the shadow itself does not make them disappear; on the contrary, they become even stronger. The more we try to escape guilt, the more we become attached to it.

This is precisely why recognising emotions and working through them in order to understand them is so important. After all, guilt is not divine punishment, but a complex emotional reaction that deserves our full attention and care. Freedom may lie in accepting guilt as part of life's premium package, but without letting it define us.

Playing ‘Master of Your Own Destiny’

We already know that guilt is something we can control, but to transform a tormenting feeling into an ally, we need time and practice. With that in mind, here are some suggestions.

Practice self-awareness

Yes. Learn to recognise and reframe your emotions, understand where they come from, question them. Identify patterns and beliefs, change them if necessary. This is the kind of work that no one can do for you.

We don't control everything

The only things we really have control over are our thoughts, feelings, and actions. Guilt often comes from the desire to control the uncontrollable, such as other people's attitudes, for example.

Learn to separate the wheat from the chaff

Question yourself and learn to recognise real guilt and discard invented guilt. Not all guilt is actually yours. Therefore, be brutally honest with yourself and separate legitimate responsibility from what is just a projection or excuse for not acting — always according to the situation.

Don't drown

When you recognise real guilt, try not to drown in it. Looking at how you feel is essential, don't ignore it, BUT don't dwell on it. Treat yourself as you would treat a loved one.

No one is perfect

A cliché phrase that means no one gets through life without making mistakes. You are the one who defines your mistakes, and when we accept that they will happen, we allow ourselves to be imperfect and automatically take a giant step towards freedom of being. So, if making mistakes is part of the show, forgive yourself.

Seek help if necessary

Therapy isn't just for ‘crazy people.’ It's 2025. Wake up! Most people suffer in silence, so it's no wonder that anxiety and depression rates have never been higher. Therapy and talking to someone who understands are your allies. Help yourself.

Develop emotional intelligence and learn to say ‘no’

Set boundaries; other people's guilt doesn't have to become yours. If you are the type of person who is a ‘sponge’ — who absorbs other people's issues — it's time to learn that this does not mean empathy.

Know the origin of things

Where or from whom is the guilt you are feeling coming from? Ask yourself. Are you blaming someone else or yourself for something real or imaginary?

No looping

Learn from your mistakes, i.e., don't repeat them. See them as a learning experience, not a sentence.

Not everything reported by the status quo makes sense

Develop your critical awareness, question norms and standards that make you feel guilty for no reason. Study, research, the world is full of imposed social guilt.

Recognise yourself before expecting others to do so

Feelings of guilt and shame tend to mask recognition of the good things we have done. It is up to us to value ourselves honestly so that we do not have absolutist thoughts. No one is 100% good or bad.

Be present in your life. Stop dwelling on yesterday or tomorrow. Those who take control of their own guilt take control of their own lives.

It's Our Fault, and We're in Control

We dare to say that guilt is a complex, malleable, multifaceted and almost inevitable human invention. But like all feelings, we can also learn to manage and redirect it. It is not a sentence or an eternal burden.

Not everything that happens around us is our fault, but it is our responsibility. Yes, the choice of how to act is always ours. We can choose to drown in guilt or surf it, and the best ways to do this are by recognising it, questioning it and transforming it into learning.

Continue exploring ‘outside the box’ ideas here on the blog. Interact if you want, comment, complain, suggest topics, question... feel free but be responsible. And for those who don't have sensitive eyes and minds, just visit our backstage UN4RT, a free space reserved for those who are truly demanding in their knowledge and critical thinking.

“The illusion crumbles when we question reality” - UN4RT

And for the smart questioners, the sources, references, and inspirations are there.

Personal experience: I have blamed others and been blamed many times. Some of these accusations were real, while others were completely imaginary. I have suffered because of them, especially the illusory ones. I have done many things I am not proud of, but regret is a word that does not exist in my vocabulary. Every lesson, every mistake, every fault served its purpose. I learned and did not repeat them. Life happens in the present, just as it is in the present that blame can be reinterpreted.

Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals.

Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince.

Socrates, The Apology of Socrates (written by Plato) and Maxim of Delphi.

Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil and The Genealogy of Morals.

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and its Discontents.

Jacques Lacan, First Writings.

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish.

Carl Gustav Jung, Man and his Symbols.

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus.

Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity and Beyond.

Comments